"a constantly touching and insightful memoir..."

— from the Foreword by JACOB NEEDLEMAN

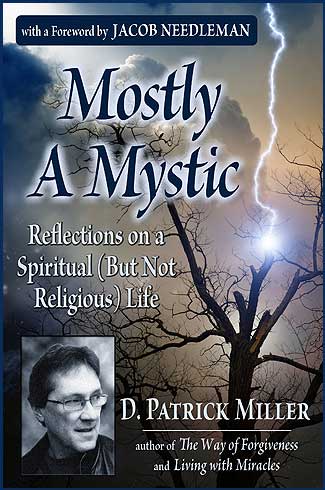

Twenty-five years in the making, the spiritual memoir of Fearless Books founder D. Patrick Miller is now available in print. MOSTLY A MYSTIC: Reflections on a Spiritual (But Not Religious) Life tells the story of how a young investigative reporter transformed into a modern mystic. Along the way, he has played a significant role in furthering the public awareness and understanding of A Course in Miracles (ACIM) as both a spiritual journalist and an independent publisher.

"I had to confess long ago that I'm mostly a mystic," says the author, "mainly because I am so often mystified." Chronicling a childhood marked by an emotionally disturbed family life and a young adulthood transformed by a seven-year illness and spiritual crisis, Miller tells a story that will reverberate powerfully with readers who have faced their own challenges in a "spiritual but not religious" age of rapid and tumultuous change. The book features a Foreword by the author's long-time mentor, philosopher Jacob Needleman.

A collection of autobiographical essays published over 25 years in such magazines as Yoga Journal and The Sun, plus new writing, MOSTLY A MYSTIC explores astral projection, disillusionment with gurus, growing up with a bipolar parent, surviving and thriving after a serious illness, the meanings of home and homelessness, ending one's religion, the expense of not selling out, and what it's like to study and practice A Course in Miracles over the long haul... as well as a lot more. For anyone who has contemplated the progress and significance of their own unconventional spiritual path, MOSTLY A MYSTIC will provide a wealth of reassurance and information confirming that you are not alone. Read sample text from the Introduction below. D. Patrick Miller has previously authored The Forgiveness Book, Understanding a Course in Miracles, and Living with Miracles, among others available in both print and digital media. His books and coaching have guided many Course students toward a deeper and more profound experience of their spiritual path. As an independent publisher, publishing consultant, and literary agent he has helped many other writers improve their work and find a route to publication.

ORDER IN PRINT & DIGITAL FROM THESE RETAILERS:

Introduction

Although the stock photo appearing on the cover of this book appears suspiciously Photoshopped to my graphic artist’s eye, I chose it because it reflects a formative experience of my spiritual life.

Eight or nine years old at the time, I was standing in the second floor den of our family’s house before a broad expanse of windows, watching a ferocious night thunderstorm soak the flood plain that lay a couple hundred feet below me, down the hill from the house. Back then, that plain — bordered on one side by a small creek that I spent much of my childhood splashing around in — was populated with about twenty-five oak, hickory, and walnut trees of at least a hundred years vintage. Every occurrence of lightning, coming ever closer, briefly illuminated them in stark relief, like the skeletons of mysterious giants standing in a wading pool, suddenly revealed in a stop-action flash.

Then, as the pelting rain softened, a strange electric buzzzz went through the room before everything I could see went totally white for a second, followed immediately by a pounding smash that shook the entire house. My mother and two sisters in the living room screamed and within seconds, it seemed, my father had rushed up the stairs from his basement workshop into the den and grabbed me by the shoulders, as if to haul me to safety – not unlike he had done about five years before when our first house, built on the same floor plan, burned to the ground. Then he had dragged me from my bedroom, half-asleep, through smoke and cinders and out the one exit that was not already consumed in flames.

This time, the fire was outside and already safely contained. We both stood there in wonder watching a few tall tongues of flame, rapidly shortening in a heavier rain, issuing from the neatly split trunk of one of the formerly tallest trees on the plain, about three hundred yards from where we stood in the den. Had the windows in front of us been solid sheet glass instead of an array of narrow panes, they surely would have shattered from the sonic impact.

In the next morning’s bright sunlight, my dad and I went down to examine the still-smoking hulk of the shattered tree. One-half had completely fallen over to the ground; the other was splintered in several standing shards, all of them seared with charcoal burns. While violent summertime weather, including the occasional tornado and flooding rains, wasn’t uncommon in the Piedmont region of North Carolina, this experience had shaken me like nothing before.

Suddenly I understood the relative powerlessness of human beings before the forces of nature that we liked to think we could control or protect ourselves from. And I understood as well how the notion of a violent, punishing God could not only have arisen in the primitive minds of early humans, but been passed on without too much reconsideration through generations of religious thought. The Biblical God I was learning about in Sunday School at that age was certainly a confusing fellow, offering infinite mercy and unconditional love at certain moments and eternal damnation at others And you could get sent to hell sometimes for what seemed like relatively minor misconduct — bad behaviors that He, after all, had provided us with the choice and capacity to commit.

Thankfully I outgrew these bewildering notions of a Lightning God within a few years, growing into a more rational if naïve agnosticism that would serve me reasonably well before lightning of a different variety struck my life in my early thirties. That lightning strike is described in detail in the chapter entitled “A Healing Catastrophe,” and it marked the beginning of my explicit spiritual path....

As a self-identified mystic, I’m both a member of an ancient esoteric lineage and a product of my times, in which more and more people are identifying themselves as “spiritual but not religious”... even when they may not know exactly what that means. I hope the course of this book helps readers understand a few things about what that identification does mean, and why it’s so significant to our culture at this time.

One of the first clues to the surfacing of the “SBNR” attitude appeared in 1988, when the decidedly mainstream periodical known as Better Homes and Gardens magazine conducted a survey on “Religion, Spirituality, and American Families.” The poll drew a whopping 80,000 responses, far more than most public opinion samplings, and included these findings:

“Some results suggest that respondents’ spirituality is strongest on a personal level. The largest group (62%) say that in recent years they have begun or intensified personal spiritual study and activities (compared to 23% who say they have become closer to a religious organization). 68% say that when faced with a spiritual dilemma, prayer/meditation guides them most (compared to 14% who say the clergy guides them most during such times)....”

It’s significant that a pre-1990s poll even distinguished between “religion” and “spirituality,” a parsing of terminology that would have been left entirely up to theologians not long before. Since that time, a number of succeeding polls have indicated that people who identify themselves as “spiritual but not religious” comprise up to 33 percent of the adult American populace, possibly higher in Western Europe, and the percentage keeps rising. This catchphrase has also entered the popular parlance on matchmaking sites, gained its own Wikipedia entry, and spawned at least one website, SBNR.org.

In the spring of 2010, a truly startling survey was released by Lifeway Christian Resources, a research and marketing arm of the Southern Baptist Convention, which might be assumed to be trolling for good news pertaining to mainstream religious practice. Instead, Lifeway’s research suggested that 72% of the under-30 Millennial generation identify themselves as SBNR. As Lifeway president Thom Rainer said, the continuance of this trend may mean that “the Millennial generation will see churches closing as quickly as GM dealerships.”

Of course, since no one has precisely defined what it means to be “spiritual but not religious,” we could be talking about little more than a vague sentiment held by an increasing number of people who can’t be bothered to support their local church, synagogue, or mosque but nonetheless don’t want to think of themselves as unspiritual. In Western culture where scientific rationality has such a powerful hold on popular consciousness, even that stingy interpretation of the data is significant. It’s more likely that people raised in the contemporary Western mindset increasingly find the myths, rituals, and rules of mainstream religions difficult to swallow, much less live by. Yet many of them have spontaneously experienced or deliberately pursued firsthand mystical experiences that cannot be sufficiently explained (or explained away) by science.

There is an enormously positive potential in this view of the SBNR phenomenon. It could signal the beginning of a mass cultural maturation in which increasing numbers of people refuse to accept either traditional theologies or reductive rationalism to explain the fundamental mysteries of human existence (chief among them being the simple question, “Who am I?”). After all, the great religions were founded in the individual visions and experiences of prophets like Jesus Christ, Mohammed, and the Buddha, who refused to accept the traditional answers of their own times, and courageously explored the ultimate “ground of being” for themselves. Their revelations were later codified into religions that were supposed to provide infallible guidance for the masses — but it can be convincingly argued that a lot has gotten lost in the translation of every profound spiritual teaching into a social religion. In the best possible light, then, SBNR signals the willingness of huge numbers of people to become their own prophets – with all the ontological hazards, conceptual detours, and spiritual bypasses that do-it-yourself enlightenment entails.

In America, we traditionally turn to religion, psychotherapy, self-help, or shopping in sometimes desperate attempts to fix our lives or soothe our souls. Starting out on an authentic spiritual path may begin with such a motivation, but eventually leads to the recognition that our lives are healed and our sanity saved not by finding the right answers to all our problems, but by learning to ask better and deeper questions about exactly who and what we are — not to mention how we came up with all these problems....

COPYRIGHT 2014 D. PATRICK MILLER. ALL RIGHTS RESERVED.

HOME • BOOKS • FEATURES • STAY IN TOUCH